The arrest of a well-known community activist in El Salvador highlights the growing risk of arbitrary detention in the Central American nation

Above: The wife of José Santos holds up a photo of her husband alongside Monsignor Oscar Romero (top right) who was killed in 1980 during El Savador’s civil war. (Credit: Manuel Ortiz)

Leer en español

In January of this year, community activist José Santos Alfaro Ayala was arrested by authorities in El Salvador on charges of gang affiliation. Santos is co-founder and president of the non-profit Tamarindo Foundation, which works to tackle issues fueling forced migration out of the Central American nation by providing faith-based educational, leadership, and economic opportunities.

Santos’ arrest is part of a sweeping crackdown justified under the “state of exception” law passed by President Nayib Bukele in 2022 and intended initially as a tool to combat gang violence. Human rights activists say it is now being used to target civic leaders like Santos. More than 2% of El Salvador’s adult population is now behind bars because of the law.

Journalist and photographer Manuel Ortiz, in collaboration with the human rights organization Global Exchange, traveled to the town of Guarjila, in the country’s rural north, to learn more about Santos’ case. What he found was a region “paralyzed by fear.”

(This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Who is José Santos Alfaro Ayala?

José Santos is a community leader who works for the Tamarindo Foundation, which began in 1992 in Guarjila, a community of just over 2,000 people in the Department of Chalatenango. He’s an athlete and serves as the organization’s recreation director, training young people in sports. He is passionate about sports, and until recently worked for the local government as director of the National Institute of Sports in Chalatenango. When I first got to Guarjila, I went around asking people about José Santos. And I was immediately impressed because everyone seemed to know him or know of him. Many described him as strict, but caring. He’s an important leader in the community and a role model for youth in a place where that is very important. This is a poor, rural region with few opportunities.

Guarjila, in the north of El Salvador, is a small community of fewer than 2,500 residents where José Santos lived and worked. After a recent murder the government deployed some 5000 soldiers to the region. (Credit: Manuel Ortiz)

Santos was arrested on January 12. What were the charges?

The Salvadoran government accused him of being linked to MS13’s Hollywood Clique, a group no one in the area had ever heard of. They offered no proof, no evidence. Soldiers arrived and handed his lawyers a piece of paper, and that was it. He remained in near-total isolation, he couldn’t speak to his lawyers, his wife, or his children. No one knew where he was or even if he was still alive. It’s important to point out that while Santos worked for the local government, he wasn’t involved in politics, but the region he comes from did not vote for Bukele and everyone knows that. Many there believe Bukele has deployed the military to the region as a message and a warning.

Can you say more about the presence of the military there?

There was a murder shortly before I arrived. Two youths were involved in a shooting that killed one person and injured another. In response, Bukele’s government deployed 5,000 soldiers and an additional 1,000 police officers to the region. Residents insist the shooting was not gang-related and that the youth involved were known thieves, nothing more. They also say that MS13 has never had much of a presence in the region.

Now, with the presence of so many armed soldiers, the fear is palpable. I attended a community meeting at Tamarindo where people spoke of the terror of arbitrary arrests. Under the current state of exception, now in its second year, the army can arrest anyone without reason and there are no legal recourses available to win their release. That is fueling a new wave of youth migration out of the country. Many ask if they can do it to Santos, whose name literally means “saint,” what might happen to them?

Soldiers have been deployed across Guarjila and the surrounding Chalatenango Department, creating fear among residents over the rising number of arbitrary detentions. (Credit: Manuel Ortiz)

You recently described the region as “tierra sin ley” or a lawless land. What did you mean by that?

Under El Salvador’s constitution, the government can invoke a “state of exception,” temporarily suspending basic rights like free speech and assembly. It did just that on March 27, 2022, after a string of brutal gang-related murders. The law is supposed to be temporary, lasting just one month. It has been renewed 24 times since it was first passed. The state, and by extension, the military and police, can now do whatever it wants. Freedom of association, the right to a defense attorney, and a speedy trial, even the freedom to communicate have all been curtailed. They can arrest anyone. People spoke of family members being targeted, sons or nephews of known activists. That is why people are afraid.

Samuel Ramírez, a coordinator with Movimiento de Victimas del Régimen, which advocates on behalf of those arrested under El Salvador’s draconian state of exception law. (Credit: Manuel Ortiz)

Were you able to confirm this?

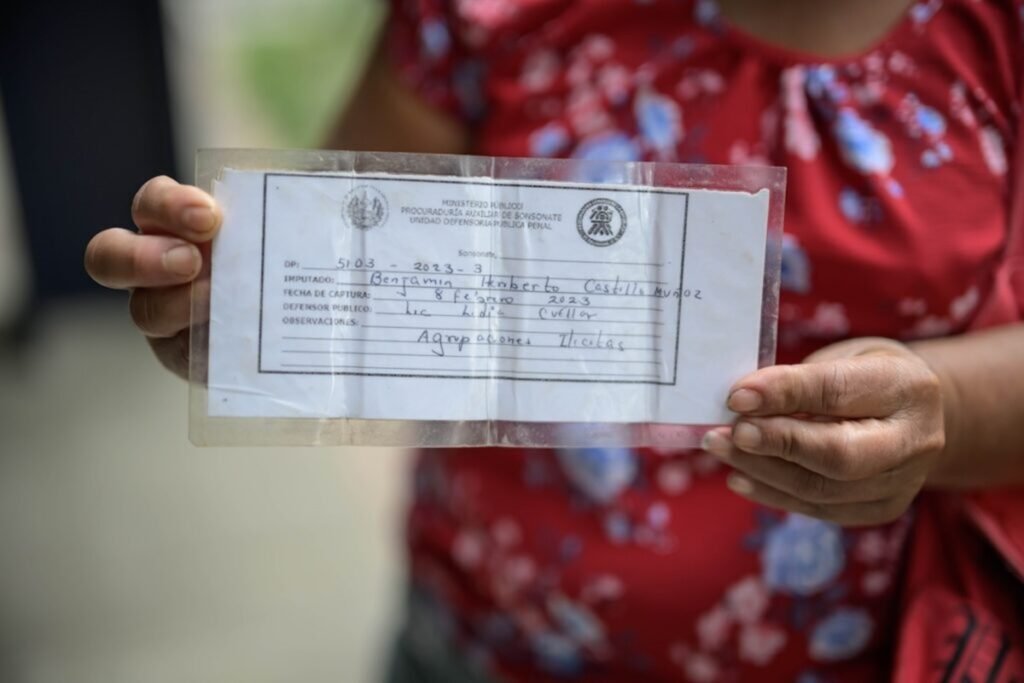

Yes, numerous human rights groups confirmed what I had heard, including the non-profit Cristosal, which just released its second annual report on human rights violations under the state of exception in El Salvador. One of its main conclusions is that the state of exception is now being used as a tool to crack down on civic groups, in part by targeting family members. I asked about this during the Tamarindo town hall, and several mothers who are active in the community immediately approached me with stories about their own sons’ arrests. They all held up papers, the same one issued to Santos’ lawyers.

A mother and community activist shows the slip of paper she received informing her of her son’s arrest. Many say the authorities are using the state of exception to target community activists and their families. (Credit: Manuel Ortiz)

In one of your photos, we see an older woman in front of an altar. Who is she?

She is Santos’s mother, Maria Carmen Ayala. I visited her and we had a short conversation. She can barely walk. She said she prays every day. I asked her to show me her altar. She started praying, she lit a candle. It was very sad. She started crying. Apart from his work in the community, Santos is also the main source of economic support for the family. So, his arrest meant they were not only heartbroken but also financially devastated.

Maria Carmen Ayala, mother of José Santos, prays before her home altar. Her son was both a community leader and the main source of financial support for the family. (Credit: Manuel Ortiz)

Bukele remains very popular, both in El Salvador and across Latin America. What do you tell people who support him?

Well, they have their reasons. First, because of the failure of past governments, either on the right or the left. And yes, El Salvador was dangerous. I had a good friend who was killed by gangs there. So, I understand the support for Bukele. El Salvador has been waiting for change for a long time, and what Bukele did was to take what had been among the most violent countries on the planet and turn it into one of the region’s safest.

But Bukele is a marketing expert. He is selling the idea that El Salvador is becoming more modern, but that is only true for a tiny sliver of the country. There’s a neighborhood in the capital, San Salvador, where he’s installed a series of neon-lit banners, like Times Square. People see this as proof of what he’s achieving. But it’s a show. People don’t understand that while he is doing this, he is defunding public clinics, public schools, and other vital institutions in rural areas across the country. Meanwhile, the economy is struggling, foreign investment is lagging, and more people are falling into poverty.

In your final days there you delivered a letter to the Attorney General. What did the letter say?

I needed to get a response from the authorities for the reporting I was doing, so on the advice of some lawyers, I decided to approach the Attorney General, Rodolfo Anotnio Delgado Montes. And what I realized was that despite all the testimony, despite all the accounts and reports issued, nothing was moving. So, I drafted a letter detailing Santos’ case. I included in the letter the organizations and media outlets I was in El Salvador on behalf of and I submitted it in person to the AG’s office. That was on April 5. On April 7, Santos’ lawyers received a letter that he was being released. On April 10, he left prison.Peter Schurmann is an editor and reporter with Ethnic Media Services in San Francisco. Manuel Ortiz is founder and editor of Peninsula 360 Press in Redwood City.